GALLERY TWO:

KEN FRIEDMAN: 92 EVENTS

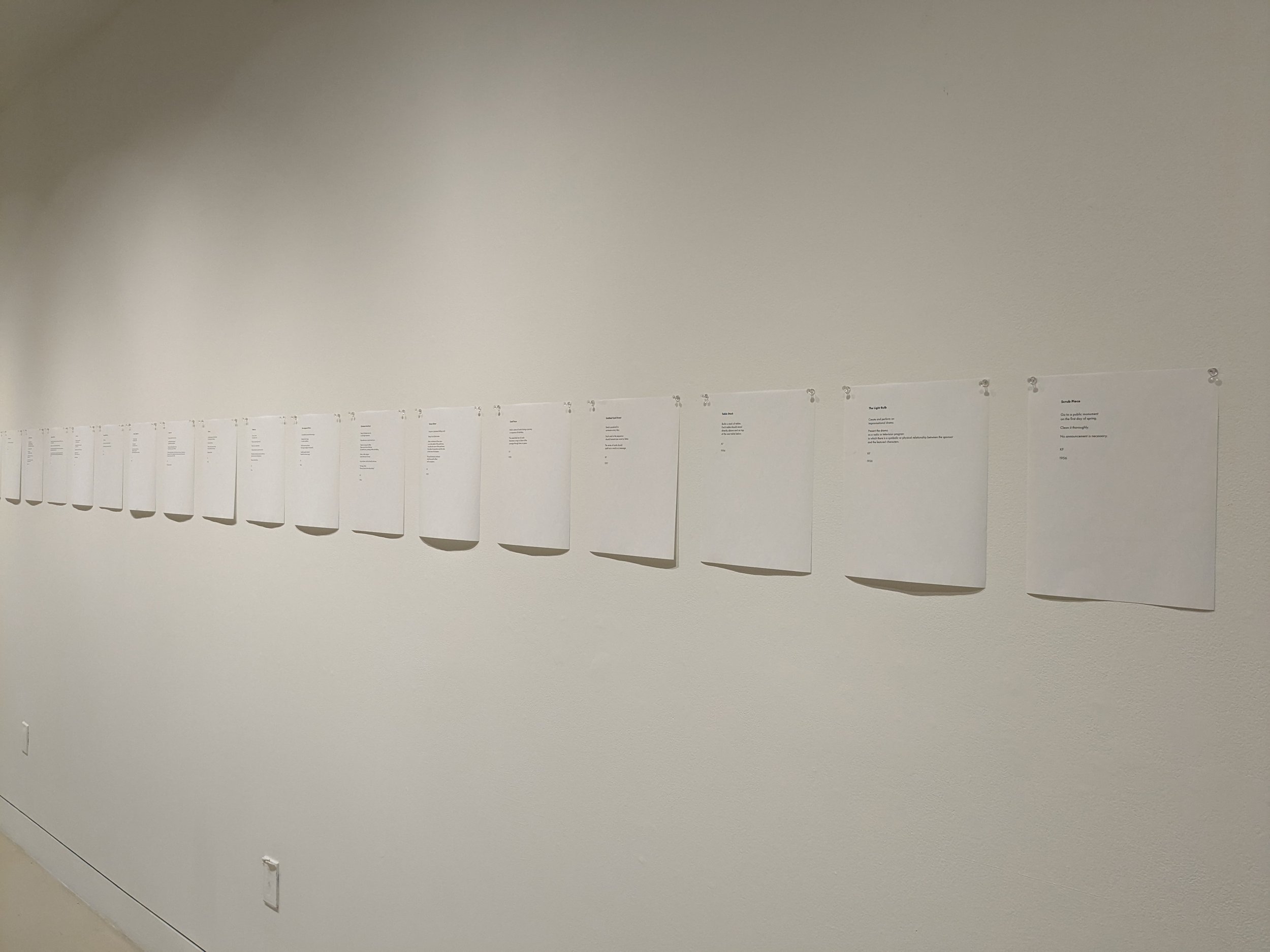

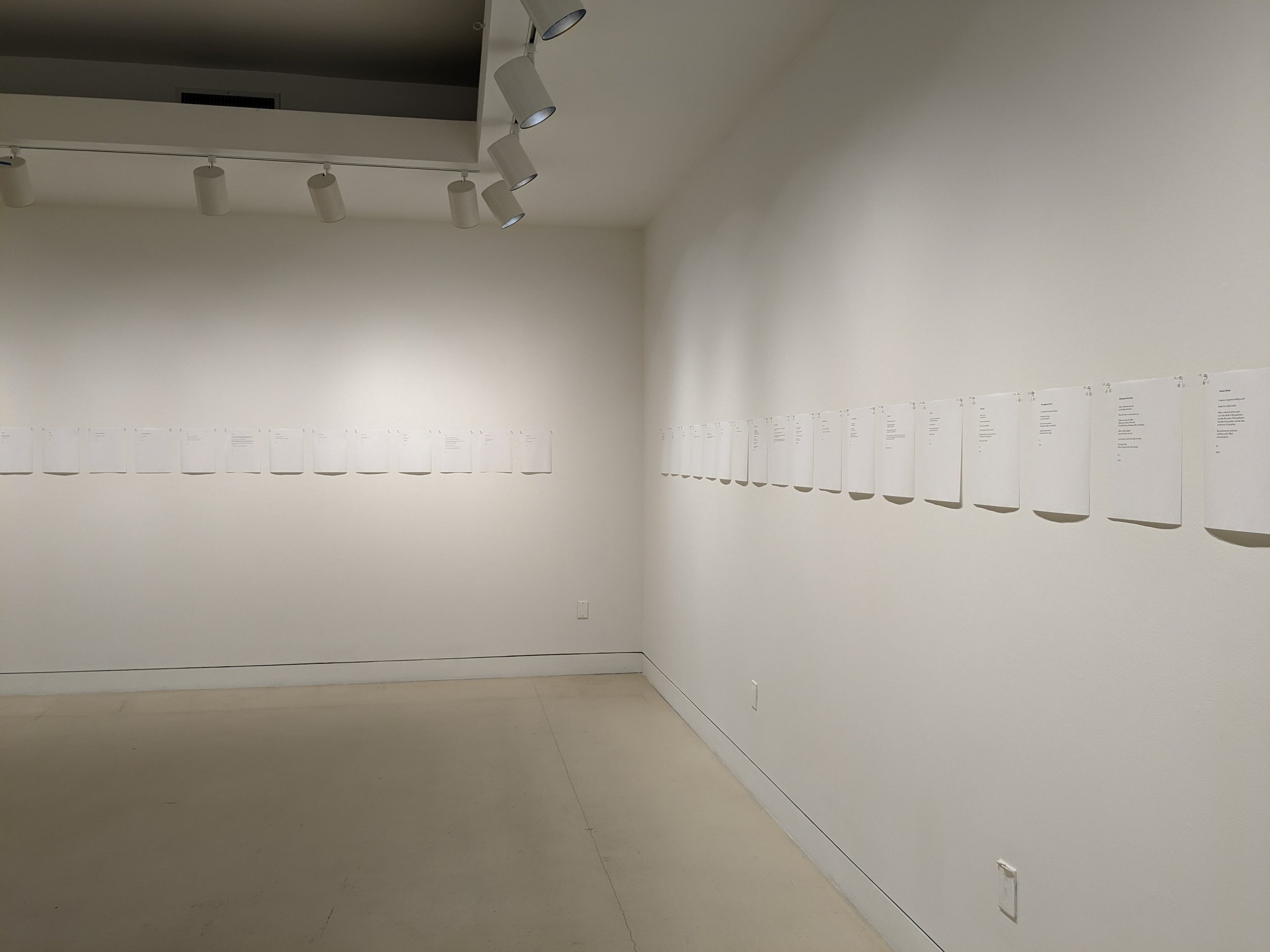

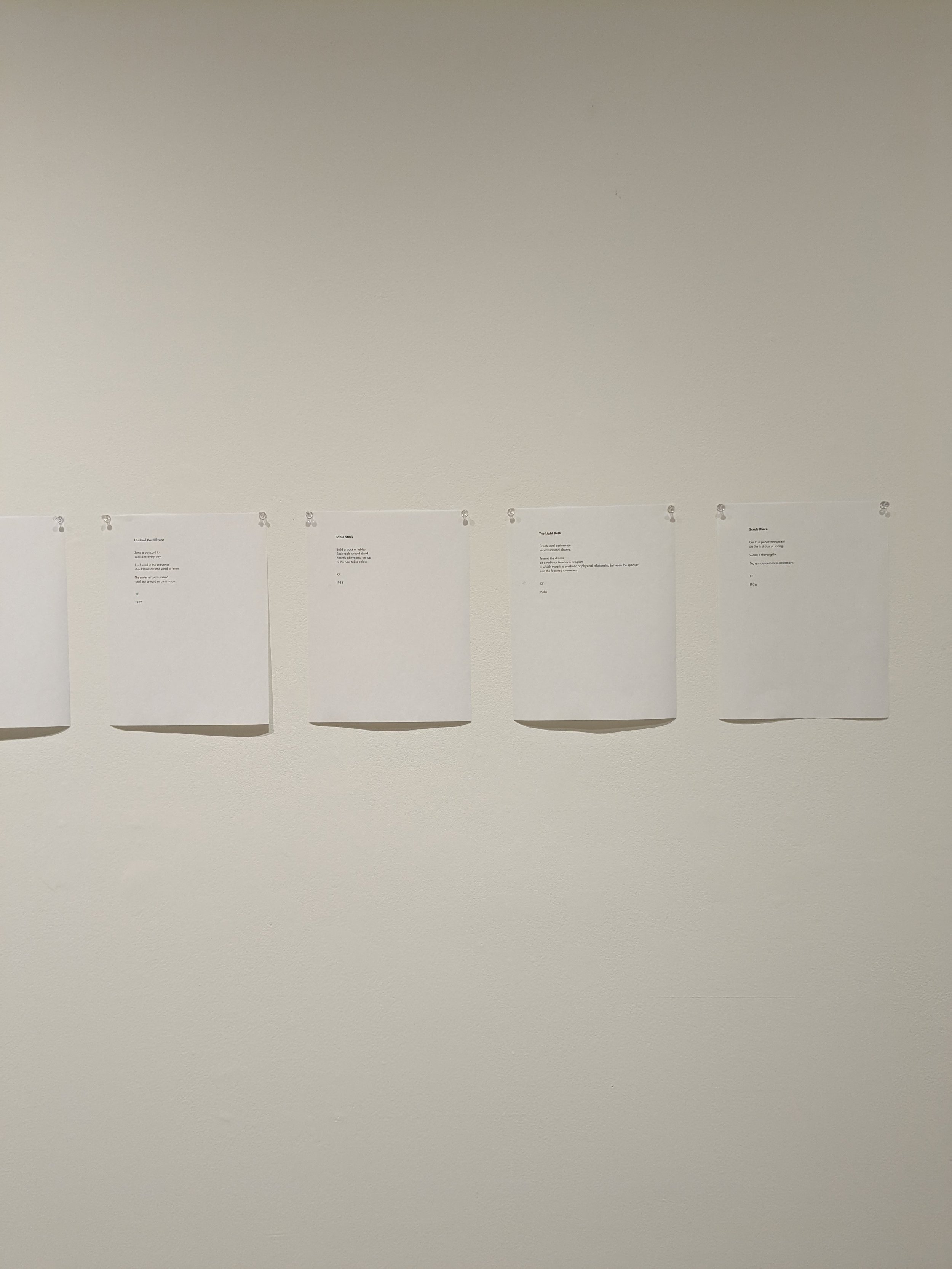

The show is based on the box of event scores that Fluxus impresario George Maciunas planned to publish. Selected scores from that collection traveled as a show in the 1970s in a set that now belongs to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Friedman continued to develop the scores after Maciunas died in 1978. 92 Events presents a selection from the original scores to the most recent. Developed in 2019, the exhibition consists of 92 event scores printed out on plain 8 1/2 x 11 inch paper. Covering around 110 feet of running wall space, the exhibit allows each visitor to take a paper sheet of the project home with them, on the closing day, Saturday December 10th at 5pm.

Exhibition Photos

Exhibition catalog

SPECIAL ART GIVEAWAY EVENT!

KEN FRIEDMAN: 92 EVENTS TAKEAWAY

FLUXUS ARTIST, KEN FRIEDMAN, INVITES TAM TORRANCE ART MUSEUM GUESTS TO TAKE HOME PART OF HIS DECADES SPANNING 92 EVENTS

92 Events presents works spanning six decades by American-born Swedish Fluxus artist Ken Friedman.

On December 10th during normal museum hours, Ken Friedman invites guest to take a work home with them.

This event is first come first serve, one per guest, and free to the public.

EVENT DATE:

Saturday December 10th, 2022

During normal museum hours: 11 a.m. – 5 p.m.

ARTIST INTERVIEW

Hope Ezcurra: You are often described as a conceptual artist. Do you like your practice described this way?

Ken Friedman: When I joined Fluxus in 1966, George Maciunas described this kind of work as “concept art.” George used the definition published in a 1959 essay -- the medium of concept art was concepts, or ideas, in the same way that the medium of music was sound. The people who made concept art in Fluxus came from varied backgrounds – ballet, cooking, printing, poetry, mathematics, philosophy, economics, architecture, engineering, chemistry, and design. Most were also involved in music, and many had studied with John Cage. Some had a traditional art background, but they were a small group within the whole, and all of them were active in this fluid artistic environment in the 1950s. This was a contrast with the people who developed conceptual art in the late 1960s. Most of those people came from a classical art background.

As with most of my Fluxus colleagues, my work began before conceptual art. The big difference for me was that I was just doing things that interested me. I was playing with ideas and actions. I wasn’t an artist or a composer. I only became an artist after George invited to join Fluxus.

HE: Do you prefer to be described as something else?

KF: I’ve never been able to decide how I prefer to be described.

HE: What does conceptual art mean to you and your work?

KF: Conceptual art interests me in the sense that art is interesting, but I’m more interested in the wider range of sources on which I draw for my work. These change all the time, depending on what I am reading. Right now, I’m reading about metrology – measurement, where measures come from, what measure is.

That has something to do with two events I have been working with lately, one about distance, one about an eight-inch cube of wood.

HE: Was there a watershed moment in your early life which made you decide to pursue art?

KF: No. I never decided to pursue art. Every time I found myself making a living as an artist, something pulled me away, sometimes for a short while, sometimes for years. But then, I drift back to art. Art offers freedom and a space to play.

HE: How did you get involved with Fluxus?

KF: In 1966, I was doing a radio program at Radio WRSB, a college station in Mt. Carroll, Illinois. I was visiting in New York in January of 1966 when I bought a copy of the East Village Other newspaper. It contained an ad for books published by Something Else Press. I decided to get review copies for my show.

When the first books arrived, I was knocked out. These were books like nothing I had ever seen before by Daniel Spoerri, Dick Higgins, Tomas Schmit, Ben Patterson, Alison Knowles, and the other artists who I later found out were part of Fluxus. I built entire programs around some of these books.

I began to correspond with Dick Higgins, the publisher of Something Else Press. He invited me to visit him the next time I was in New York. I wound up staying in a little room off of Alison Knowles’s studio upstairs from Dick’s apartment.

One morning, I made a little box for Dick. I made the first version of the box in December 1965, while I was at a meeting at the First Unitarian Church of Chicago. I took a large matchbox that had been filled with wooden kitchen matches. I covered the outside with paper and printed the words, “Open me” on the outside. On the inside, I printed the words “Shut me quick”.

Dick thought Fluxus impresario George Maciunas would like it, so he called George to introduce me. George did like it – in 1966, it became my first Fluxbox, The Open and Shut Case.

That’s how I became involved with Fluxus. George’s telephone directions brought me to his fifth-floor walk-up apartment on West Broadway. It was in a decaying industrial section of New York City that was part of what was then Little Italy. I walked up the stairs to find a black door covered with violent, emphatic NO! SMOKING!!! signs. I

knocked.

The door opened a crack, and a pair of eyes framed in round, wire-rimmed spectacles peered out. That was George. George Maciunas was a small, wiry man with a prim, owlish look behind those spectacles. He was dressed in a short sleeve business shirt, open at the neck, no tie. He wore dark slacks and black, cloth slippers. His pocket was cluttered with pens.

George ushered me into his kitchen on a steamy, New York summer day. The apartment was cool. It smelled like rice mats. I recognized the smell. It reminded me of a Japanese store I used to frequent as a youngster in New London, Connecticut.

The apartment contained three rooms. To the right was a compact, well-designed office and work room.

Off to the left was a huge, walk-in closet or a small storage room. The room was filled with floor-to-ceiling shelves, like an industrial warehouse. It was an industrial warehouse, the comprehensive inventory of Fluxus editions in unassembled form. The shelves were loaded with boxes storing the contents of Fluxus multiple editions, suitcases and yearboxes. When an order came in for a Fluxbox, George would go to back of the closet, select the right plastic or wooden container, and march through the room plucking out the proper cards and objects to emerge with a completed work.

He’d then select the proper label, glue it on and have the completed edition in hand, ready to mail.

The kitchen had a sink, windows, stove, table and chairs, all quite ordinary except for the refrigerator. George had a bright orange refrigerator. When he opened it, I could see he had filled it with oranges from the bottom clear to the top shelf. The top shelf, on either side of the old-fashioned meat chest and ice tray, held four huge jugs of fresh orange juice. He offered me a glass of orange juice.

George peppered me with questions. What did I do? What did I think? What was I planning? I was planning to become a Unitarian minister. I did all sorts of things, things without names, things that jumped over the boundaries between ideas and actions, between the manufacture of objects and books, between philosophy and literature. Maciunas listened for a while and invited me to join Fluxus. I said yes.

A short while later, George asked me what kind of artist I was. Until that moment, I had never thought of myself as an artist. George thought about this for a minute, and said, “You’re a concept artist.”

I like the fact that I became part of Fluxus before I became an artist.

HE: How did the collaboration with your fellow Fluxus members affect your work and vice versa?

KF: That’s such a big question that I can’t answer it. It’s like asking a fish about swimming in the sea. I continued doing all the things I was doing. What changed was that I did them in a new context. Before I joined Fluxus, I was simply myself doing these things. Now I did the same things in the context of a community of people who did similar things.

It’s difficult to say how my work affected the others. They already knew each other, and they had a well-established global community. I was someone new, a name on George’s mailing lists, someone who did things with their work in California and the Western United States.

It’s hard to say how what I did affected them. I wish I had asked.

HE: What do you think the repercussions of Fluxus have been on contemporary art currently?

KF: Fluxus has had enormous impact on contemporary art, but that impact has only begun to be recognized recently. It’s come about thanks to a new generation of art historians. It started with the first major history of Fluxus by the late Owen Smith. Today, a number of outstanding scholars have come to specialize in Fluxus studies. These include Hanna Hölling, Colby Chamberlain, Natasha Lushetich, Natilee Harren, Martin Patrick, Roger Rothman and others. As I read some of the excellent new books and articles coming out, I find myself thinking about Fluxus in new ways.

After half a century, things take on a new light – things that were neglected or unseen come into a new perspective. While Fluxus was far more influential in the 1960s and 1970s than was recognized at the time, the art market determined how things were seen, and nearly none of us had the kinds of skilled dealers to bring our work into a market perspective. Of course, we didn’t make saleable things in a reliable way, so we didn’t fit the market, either.

Today, Fluxus is finally getting its due. But it’s hard to say what that really means.

HE: What was your initial inspiration for the 92 Events?

KF: In the 1960s, I made a show of event scores that traveled widely around the world. It was titled Events. It opened at the Nelson I.C. Gallery of the University of California at Davis in 1973. Over The next decade, it was exhibited in many places. It could go anywhere in the world for about ten dollars – the cost of making a copy and mailing it. For that show, I selected a group of event scores that George planned to publish in a Fluxus box. At the time, I chose scores from my first event in 1956 up to the time of the show.

92 Events is based on the same idea. I chose scores from that first 1956 event – Scrub Piece – up to the time we assembled the show.

HE: How often do you make an event?

KF: In the 1960s and 1970s, I was travelling, exhibiting, and performing all the time. Because of that, I created event scores often. These days, I think for a long time between each event score and the next.

HE: What are the criteria in making them?

KF: There is no special criterion. There never has been. Ideas come to me in different ways. Perhaps they arise in a situation or emerge from the world around me. Perhaps I’ve been thinking about a puzzle or a question. The idea becomes the seed of an event. If it stays with me, I polish it and develop it.

Each event score has a life of its own. Sometimes I rethink an event or change my mind about it.

HE: Do you have a favorite event, and if so which?

KF: I have different event scores that I like a great deal, but they change. I’ve never had one favorite event. Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about a score from 1971. This is the score about distance that I mentioned:

“The distance from this sentence to your eye is my sculpture.”

The other score I’ve been thinking about a great deal is a 1968 score for an object titled Stumbling Block.

It’s an instruction to make a wooden cube 8 inches on each side.

An artist friend in Florida named Sean Miller acquired some tropical hardwood, so he’s been producing the Stumbling Block as an edition.

The event that is most on my mind at any time is my favorite at that time. That makes sense for an art that is made of ideas.